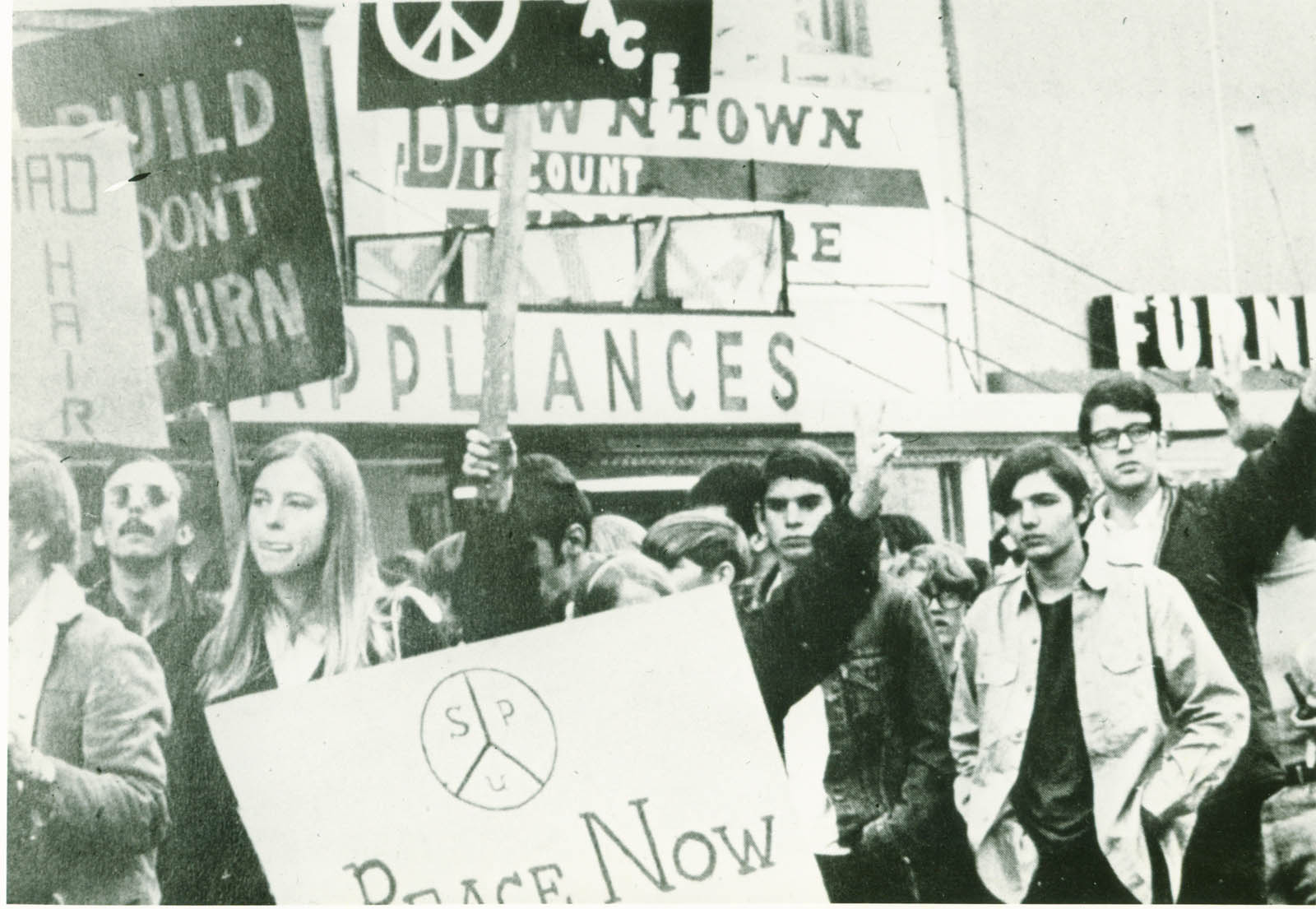

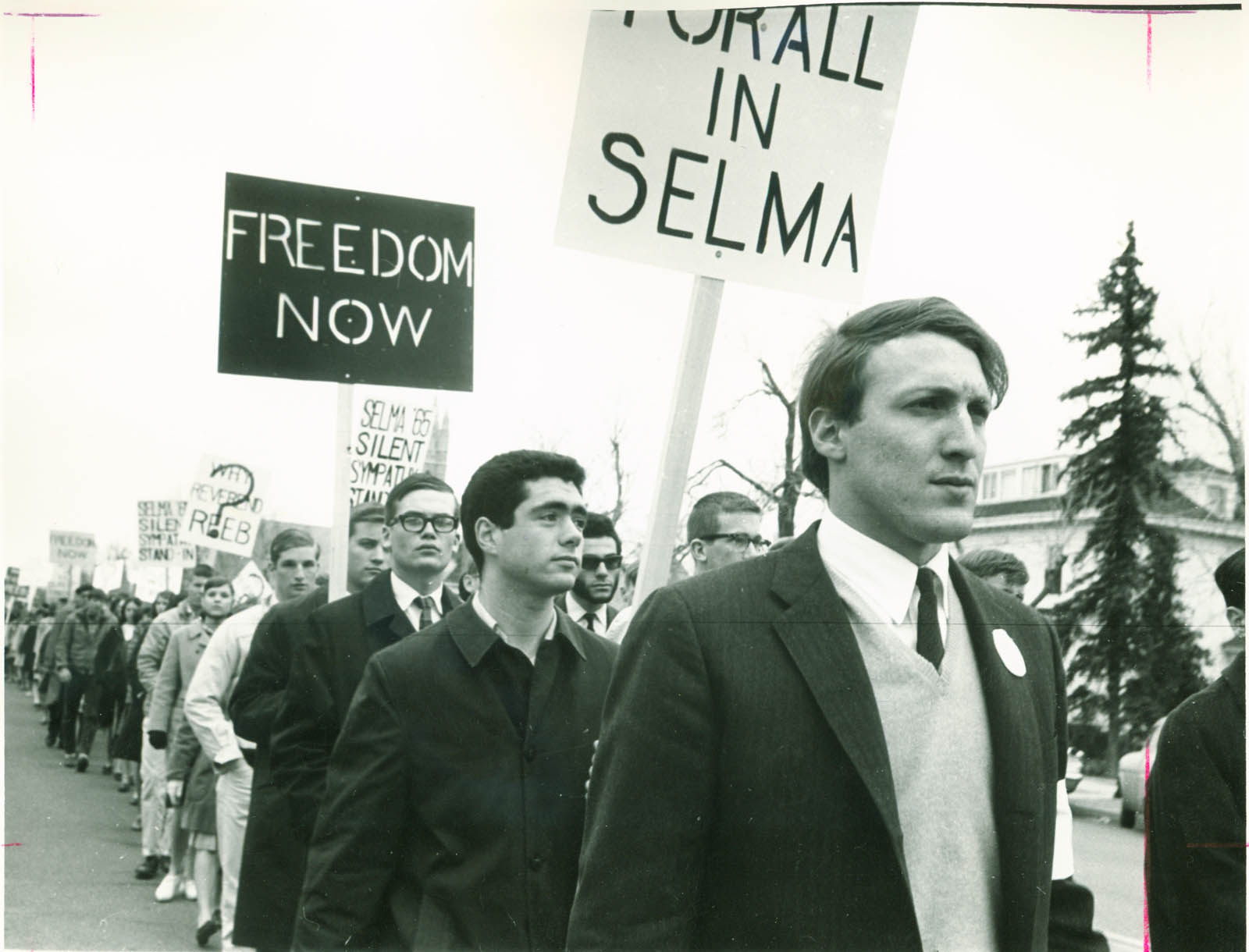

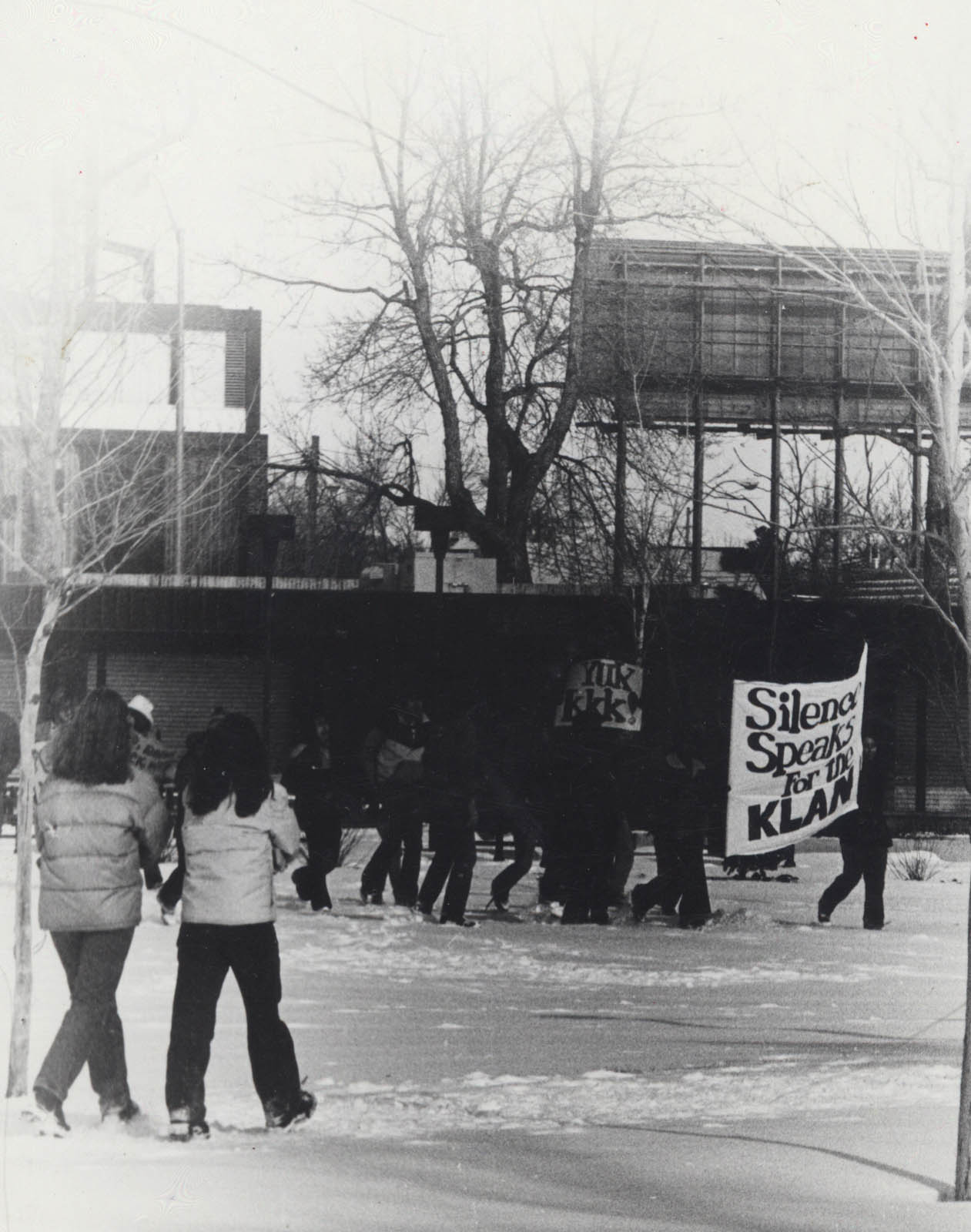

Student activism had long been central to the liberal arts experience at Colorado College, and during the 1960s and early ’70s, students began engaging in new ways with social justice issues beyond the scope of CC’s campus. Many CC students challenged the ROTC program and the fraternity-sorority system, called for reform of the student judicial system, and advocated for racial justice. Both students and faculty marched on City Hall to protest the racism and police violence perpetrated against Dr. King and other Black activists. They protested the war in Vietnam, leading weekly vigils at the Earle Flagpole, and led anti-war marches to downtown. They were joined by faculty on multiple occasions in their protest at the Fort Carson military base South of Colorado Springs.

It was amid this environment of tension, controversy, and young adult activism that CC’s Block Plan was born.

Some alumni reflect that college leadership was for the most part supportive of students' activism, “so long as we didn’t burn anything down,” Les Goss ’72 says. He participated in the anti-war efforts at CC as a student, and was granted conscientious objector status in protest of the war.

“Being on an urban college campus, we organized many sit-ins, blocking traffic on the intersections of Cascade and Cache La Poudre, or Uintah and Nevada, to protest the war and make our message seen and heard beyond CC,” Goss recalls.

A cultural shift to freedom of thought was also reflected in innovations to Colorado College’s academic program. Among numerous changes to course requirements, the college instituted an Honors/Pass/No Pass grading system and, after a good deal of debate allowed men and women to visit one another’s dormitories.

Yet many professors and students alike still saw new opportunities to develop CC’s academic program. They saw that students were overworked and siloed taking five or more courses at a time on the semester program, and proposed a 4-2 model, in which students would take only four classes a semester. But when it came time to vote, the faculty turned down the proposal three to one. Looking back, the 4-2 system — which had already been adopted at Harvard and other institutions across the country — was not that radical a proposal. But some thought that was the problem — it was a change, but not enough change.

Knowing that Colorado College was six years away from 1974, its 100th anniversary, Professor Fred Sondermann suggested to CC’s ninth president Lloyd E. Worner ’42 that the faculty find a way of not just celebrating the last 100 years, but do something that would look forward to the next. This led to a college-wide effort to take a critical and reflective examination not only on CC’s academic past, but also its future, and Professor Glenn Brooks was tasked with leading the project. Brooks began the planning process in October 1968, soliciting ideas and feedback from the CC community. Initially there was no plan, only possibilities. Much of the feedback Brooks received underscored “the need for greater immersion, the need for smaller, personalized groups of students and professors.” Brooks drew on inspiration from his colleagues who had proposed the 4-2 model, but dared to go further. By the end of January 1969 he had prepared a proposal for only one immersive class at a time, with nine courses each academic year. That spring Brooks installed a proposed schedule and invited students in to see if they could plan out a year on the new system.

“We had radical students involved in working on this plan...because they had a sense that something was going to happen,” Brooks shared in an oral history published in February 1996. “This probably couldn’t have happened if there hadn’t been such an atmosphere of change, educational and cultural change, in society.”

Then it was, as Bryan Adams famously said, “the summer of ’69,” and indeed the times were changing. The counterculture movement came to a head at Colorado College with the now-infamous production of “Dionysis in 69.” The play, performed by an experimental theatre group from New York City, was part of CC’s 1969 symposium on violence. The play was an adaptation of Euripides’ ancient Greek tragedy “The Bacchae,” and was performed nude. However, for this particular performance, CC’s administration was promised that the actors would remain clothed for the duration of the performance.

“Well, within two minutes, they were naked,” remembers Goss, who drove to campus with his friend from his home in Denver to see the performance, knowing little prior about the production. “They were out of tickets, but we got to watch backstage from the wings. It was truly a spectacle.”

As one might imagine, CC became the center of a public relations nightmare, with the ensuing outrage and horror expressed by many members of the Colorado Springs community.

Rather than divide the CC community, this brought the campus together; many faculty and alumni alike reflect that this play and ensuing outrage served as a catalyst for cohesion within the CC community. This was largely due to the open-minded response of President Worner, whose position was steadfast in defending the performance on the basis of free speech and freedom of expression. Students were enthused by Worner’s tolerance, even gathering at the flagpole to show support of their administration’s response. During a time of division between many students and their college administration, CC students were protesting for theirs. It was an eventful summer indeed that preceded the Block Plan’s implementation.

Brooks announced the Master Plan at CC’s 1969 Fall Convocation, the faculty voted to approve the proposal 72 to 53 that October 27, and the college would adopt the new academic program the following fall.

The Block Plan was more than a new academic program; it became a cornerstone of collective identity.

The Block Plan immediately proved effective in its ability to connect academics with life outside the classroom. Students in Professor Emeritus John Lewis’ Introduction to Geology course spent a majority of their time performing field study research at geological sites across Colorado, learning more from the geologic structures that were literally at their fingertips than they might have from a textbook alone. Professor Emeritus of Political Science Robert Loevy taught a one-block course, Political Campaigning, during which students worked for a political campaign of their choosing for academic credit. Students traveled across the nation to campaign, in the hope that they would impact the 1970 Congressional election. The course remained popular well into the late 1990s, garnering student engagement in various elections over the years. Block breaks offered students the opportunity to explore the Southwest by car, by foot, or even by bicycle, or students relaxed on campus and got to know the city.

“Learning in a small liberal arts environment on the Block Plan challenged me and taught me to open my mind,” shares DeeDee Dehning Loomer ’72, who went on to earn her MBA after attending CC during a time when “I was told by my high school counselor that I ‘would make a great wife and mother if I had a college education,’ but Colorado College truly shifted the scope of my ambitions and how I see the world.”

In the 50 years since its founding, CC’s Block Plan has come to represent an alternative path for learning, attracting curious students who are drawn to this singular academic experience as much as they are enticed by the college’s distinctive sense of place. And even amid an ongoing pandemic that has required institutions across the country to shift to remote and hybrid academic instruction, Colorado College students continue to organize and advocate, fighting for change on their campus, across the nation, and across the globe.

For further reading on the history of the Block Plan, see “The Block Plan: An Unrehearsed Educational Venture” by Susan Ashley.